Sarek: the final frontier

When

Mar 27 - Apr 6, 10.5 days of skiing.

Where

From Ritsem (actually ~18 km south of Ritsem) to Kvikkjokk, zigzagging through Sarek for ~190 km. So why is Sarek "the final frontier", tongue in cheek? Because of the way it is often presented in tourist brochures: Scandinavia's largest wilderness; pristine nature with no huts, bridges, marked trails, or emergency services; the ultimate challenge for experienced hikers, etc. In actual fact, the entire national park is at most 60 km across, and going through it from Ritsem in the north to Rapadalen in the south (and from there east to Saltoluoka or south to Kvikkjokk) is quite easy to do and requires just a few days under ordinary weather conditions. I believe that's roughly what most groups do in Sarek: I met several teams in the central valley, but then didn't see a soul - or even as much as an old trail - anywhere in western Sarek or on the plateaus. In other words, you can have your Sarek in different ways - easy-going or hard-boiled, up to you - but even a simple transit is definitely a very different sort of experience compared to following a marked trail like Kungsleden.

And then there is a second reason I'm talking of "final frontiers": I personally set my sights on Sarek for a solo winter trip as early as 2017. That time I started out from Kvikkjokk on my first ever skiing expedition with narrow cross-country skis, a flat tarp, and a heady excitement of taking a plunge at the deep end with very little preparation. Fortunately, I was quickly disillusioned after the first night of shivering and plodding 50 m from the trail into the woods to pitch my tarp amid waist-deep powder, so that year I gave Sarek a wide berth and then practised for a few years on less technical routes such as Hardangervidda in Norway and different variations of Kungsleden (2020 and 2021). Solo winter trips do take some trial-and-error: it takes time to compile the right gear kit and acquire the know-how for staying safe and comfortable. This year the stars were favorable, I was ready, and the trip worked like a charm.

The plan was simple: I was not concerned with going from A to B or doing a lot of miles. Instead, the idea was to follow flat-bottomed valleys in Sarek on days without visibility and to have as much randonnee-type fun as possible on days with visibility. I also consciously avoided taking risks or pushing myself too hard - instead, I gave myself a few more days than strictly necessary, making it possible to wait out bad weather and generally to be flexible with route selection.

Weather

Snowing and blowing 9 days out of 11 (with some hours of sunshine here and there), completely clear on 2 days. Elevation 300-1500 m, temperature about -20°...0°C, usually about -5° to -10°C. It was somewhat less windy than I am used to, maybe 1-5 m/s except a couple of days with winds up to 20 m/s. Unfrozen water: practically none, except in Rapadalen and towards Kvikkjokk; I almost exclusively melted snow, up to 3-4 L/day.

Trail: none in Sarek except for a few kilometers at the borders (south of Ahkka and in Rapadalen just before Aktse). Snow conditions: very variable. There was ice or even bare rocks in some valleys, and then just around the corner there would be deep powder. On average, and especially in view of constant snowfalls and the nearly complete absence of a trail, I spent an enormous amount of time and energy breaking trail through powder or - even worse - through semi-consolidated crust. The average speed was therefore very slow, and sometimes as much as 8-9 hours of exhausting work was needed to advance a mere 15-20 km. Still, I shouldn't complain because a major thaw over the weeks before my arrival had created a strong icy crust, which provided a reliable foundation despite being gradually buried under feet of fresh powder.

Equipment

8 kg base weight + 8 kg of food and fuel. Skis: the good old trusty Fischer S-bound 112 mm with Easy Skins for climbing. I absolutely love these skis: too short and broad to be efficient on groomed trails, but fantastic for breaking trail and dealing with steep terrain, especially in deep snow. Bindings: Voile Traverse (3-pin), without cables. Boots: Fischer BCX6 3 pin 75 mm - telemark boots with soft uppers and external skeleton for better control of skis on descents. This was the first time I'd tried these boots, which I unexpectedly snatched on sale last summer in a last-ditch attempt to impove the wellbeing of my poor feet, which had been squeezed into a pulp in the plastic boots I used on my last three winter trips. And, o dio, it worked! I can't believe it - I got back after 11 days of skiing without a single blister. OK, so BCX6 boots are not quite so waterproof and stiff as plastic boots, but the gain in comfort was incalculable. Notably, I got size 46 - a full two sizes above what I normally wear, but the extra room proved extremely comfortable and let me use double socks + a vapor barrier without squeezing my feet. And yes, these boots are sufficiently stiff to drive fairly broad skis. In terms of cons, it's harder to keep the feet dry and warm when there is no removable insert, the boots freeze solid on cold nights, and there are already some cracks in the uppers after just this single trip. Bottom line: not a perfect backcountry boot, but anything to avoid pressure points. Pain-free feet = a happy hiker.

Shelter: as usual, a simple, single-layer, floorlees, silnylon pyramid tarp in reasonable weather and snow caves in really bad weather. Among the new items that I was really pleased with this year, I would note a really warm and weather-proof parka (800 g, insulated with 200 g/m2 of Climashield) and polarized skiing goggles (actually, a lightened version of goggles for surfing, 55 g). They improved my vision tremendously not only in bright sunshine, but - incredibly - also in overcast weather and especially during snowfalls. Don't ask me why, but it turns out to be easier to read the snow when wearing them - highly recommended. For more details on the equipment and food used on this trip, see spreadsheet.html.

Logistics

There: trains and busses to Ritsem. Back: trains and busses from Kvikkjokk. It's a terrible journey both ways (the trip back took over 30 h, including a 10-h bus ride from Jokkmokk to Östersund). Trains get delayed, bus connections are missed, etc. The bus to Ritsem actually went off the road and got hopelessly stuck in a snow drift, which is why I began the trip 18 km further south than planned (see below). So in that sense Sarek is definitely remote, and it's a lot easier to start in Abisko instead.

Maps

Paper map: Calazo Sarek & Padjelanta, 1 km. Offline maps on the phone via Oruxmaps. Online topographic maps here.

Days 0-1: trailhead to Sarek

The last connection on the way to Ritsem is to change from train to bus in Gällivare. And, of course, the train was delayed, the bus was supposed to wait but did not, and there we were - about a dozen rugged and eager adventurers with bulky backpacks and a pair of skis each, waiting at the bus stop and joking about public transport. Strength being in numbers, a replacement bus was eventually arranged, and I breathed in relief - I had concluded long ago that the most stressful part of most hikes was the journey to the trailhead and then back home again. An interesting development, though: the minibus went off the road and got stuck in the ditch. Well, no problem, there are advantages to transporting hikers: every passenger pulled on warm mitts, extracted a snow shovel from their luggage, and started digging - the very dream of every long-haul bus driver:

After half an hour of digging and trying to get the bus back on the road, it had only slid another meter off the road. As the map showed that the mighty lake of Ahkajavrre was a mere 3-4 km across at that point, it seemed reasonable to cross there instead of trying to reach Ritsem itself. The point with going to Ritsem in the first place was that there was a marked crossing there - a safe route over the ice. However, the lake looked to be frozen solid and not too broad, so me and an exuberant Norwegian with a pulka said goodbye to the stranded bus and its embittered driver, put on our skis, and set off there and then. The ice proved to be completely solid, so we crossed without any mishaps and then parted company: he headed north to the beginning of Padjelanta trail, and I started to climb west towards Ahkka and Sarek.

Stage 1 was therefore successfully completed: crossing Ahkajavrre went off without a hitch. What I seriously underestimated, however, was the difficulty of climbing from this huge lake (elevation ~430 m) to the plateau leading into Sarek (~900 m). The immediate shores were a mixture of gigantic bare boulders and the softest fresh powder - so soft that I repeatedly scratched my skis when they sank right throw the snow onto the razor-sharp rocks. Between the boulders, on the other hand, the drifts were absolutely bottomless, making it impossible to walk on foot to spare the skis. I camped on the slopes after advancing a mere 2-3 km after hours of back-breaking scrambling. Worse still, it kept snowing throughout the night, further increasing the depth of powder. Fortunately, there was some wind the next day, and some sort of weak crust was gradually forming above the tree line. Even so, I would definitely NOT recommend this route to Ahkka: it's got to be easier to start in Ritsem after all, like most everyone does.

It took me the entire next day to do ~17 km to Ruohtesvagge: the deep, narrow valley that leads from the peak of Ahkka south to the heart of Sarek. Despite the intermittent snow and wind, there was enough visibility to find the way and take a few photos of this rugged area:

-10°C and blowing. A balaclava and warm parka make a huge difference when resting, although the tiny sliver of my face that was exposed still got slightly frost-bitten on the last-but-one day of the trip:

The steep-sided Nijak (1920 m) provides a distinct visual landmark:

A good view of Ahkka (2011 m). Many groups going through Sarek south-to-north finish the trip by summiting it:

Days 2-3: crossing Sarek without seeing Sarek

The weather seemed to be clearing up nicely towards the evening of day 1, but my hopes for sunny weather were crushed: the next two days it snowed almost non-stop, I was in and out of low clouds, and visibility was minimal. In effect, I crossed most of Sarek in these two days, first following the main north-to-south artery through which all groups seem to pass, and then turning into a smaller valley that leads west to Padjelanta national park. Progress was initially slow, but then for a few hours I followed the trail left by some other groups, which was so fast and easy that it felt like hitching a ride compared to the slow plodding through unbroken powder. I overtook two groups heading south, and by the time the trail had disappeared (it was snowing and blowing steadily), I was approaching the only emergency shelter and the only bridge in the very heart of Sarek.

Typical views in the rare moments when the clouds momentarily lifted:

In the evening I stumbled across a locked hut of deer herders and pitched my tarp in its lea, hiding from the fierce wind and drifting snow. The next day there was even less visibility, any kind of summiting was out of the question, so I just continued as best I could along the flat valley of Algavagge west towards Padjelanta. From day 2 and for an entire week I didn't meet anyone and saw no trails of any kind, so I had to break the trail through fresh snow every inch of the way. I worked steadily, trying to spare my knees by letting them bend freely on every step instead of forcing my feet forward through the snow - a nice if somewhat counter-intuitive technique, which knocked off the discomfort that I was beginning to develop in the tendons. The long hours of daylight also helped tremendously: it was possible to do very long days, up to 12 hours from camp to camp, without worrying about getting caught in the dark. I was also dressed warmly enough to take long breaks, including two unhurried meals about half an hour each. Combined with blister-free boots, all these small tweaks in the hiking style and equipment enabled me to be infinitely more comfortable this year than I was on my previous trips, so I could do longer hours and yet feel less fatigue, both mental and physical.

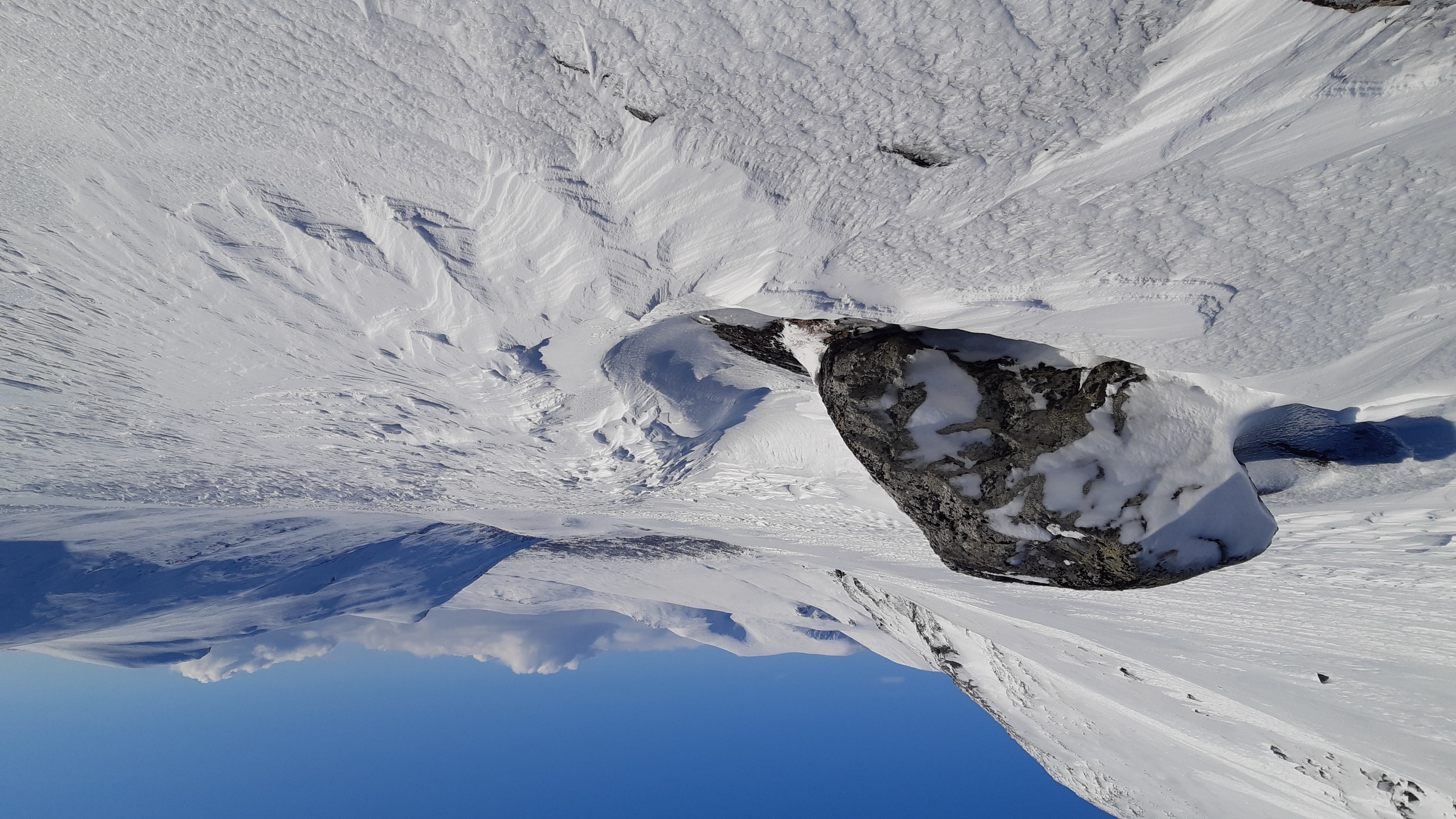

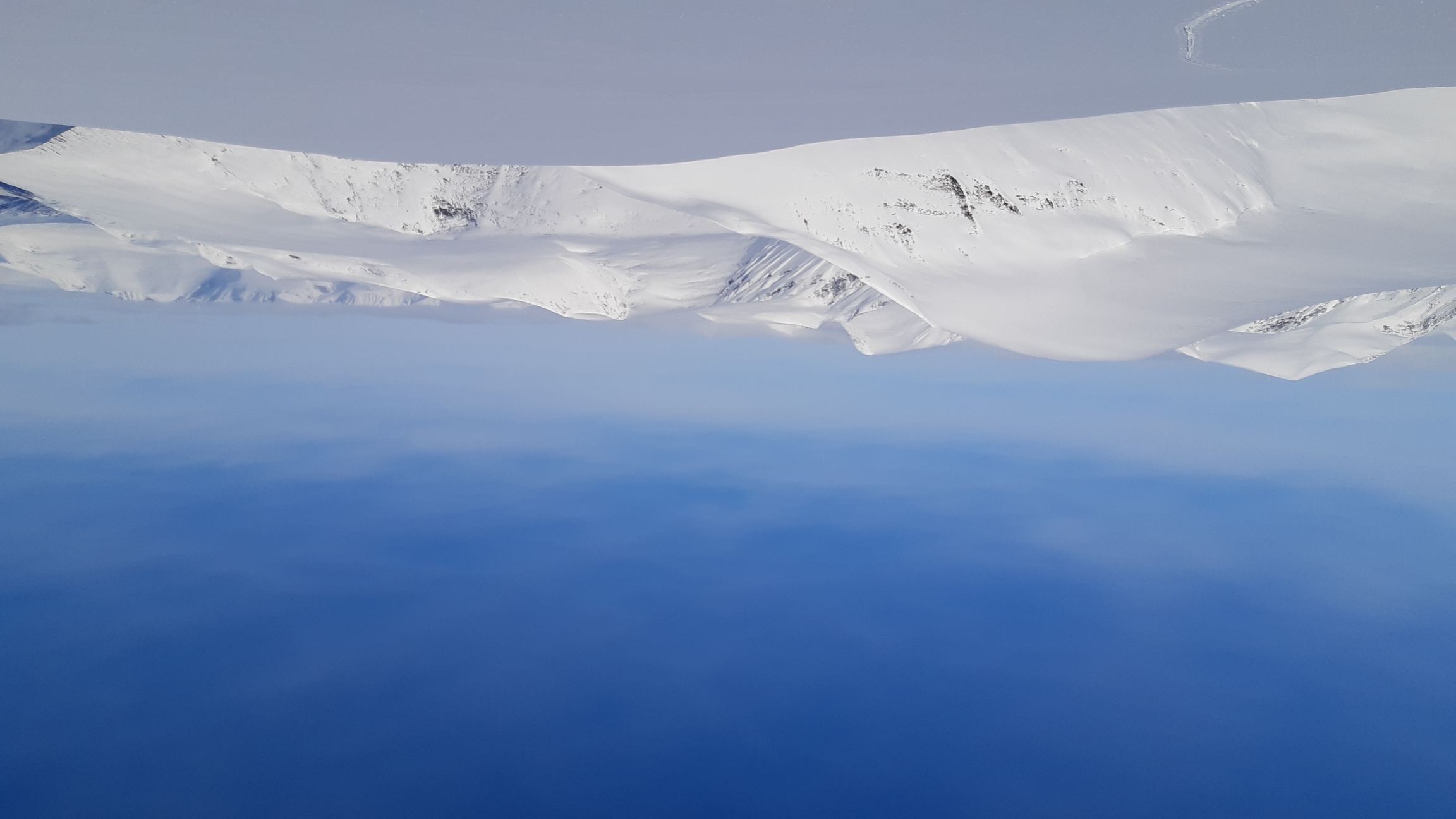

Two foggy days later I had done about 40 km through Sarek itself, basically crossing it from Ahkke in the north to the border between Sarek and Padjelanta south of lake Alggajavrre. For a few kilometers I followed the tracks of what was either a large elk or a small elephant, climbed over a little bluff next to lake Alggajavrre, and found myself looking west into Padjelanta national park. The snow suddenly stopped falling, the clouds began to lift, and the black-and-white beauty of the place was revealed in a symphony of light and wind:

Days 4-5: clear skies beckon up

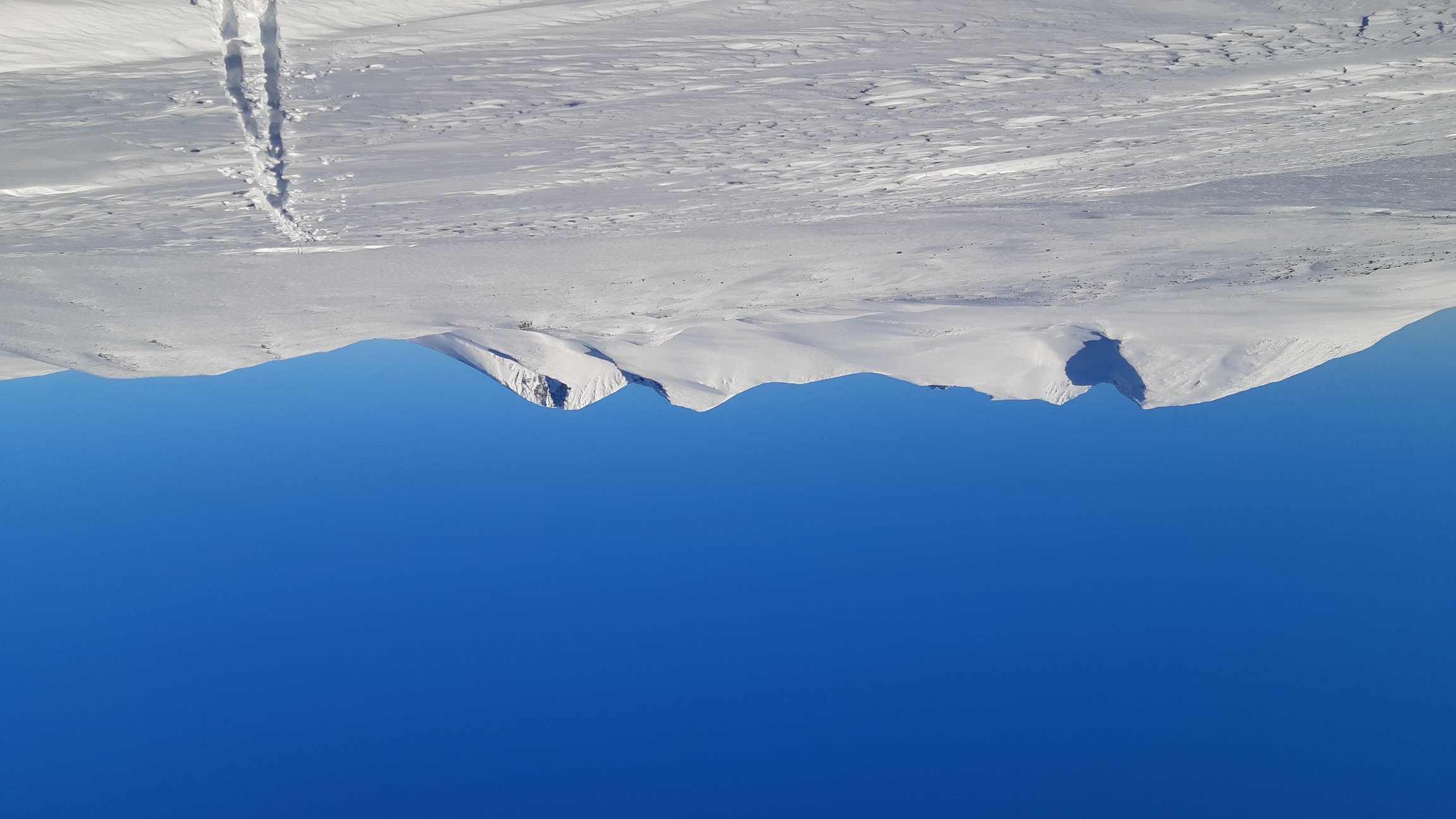

Two sunny days - two day marches to fill with adventures. Of course, you never know whether the sun would shine for a day or just for half an hour - mountain weather is fickle. But I was cautiously optimistic after the last remaining clouds dissipated towards late morning of day 4. Sunrise over Sarvesvagge:

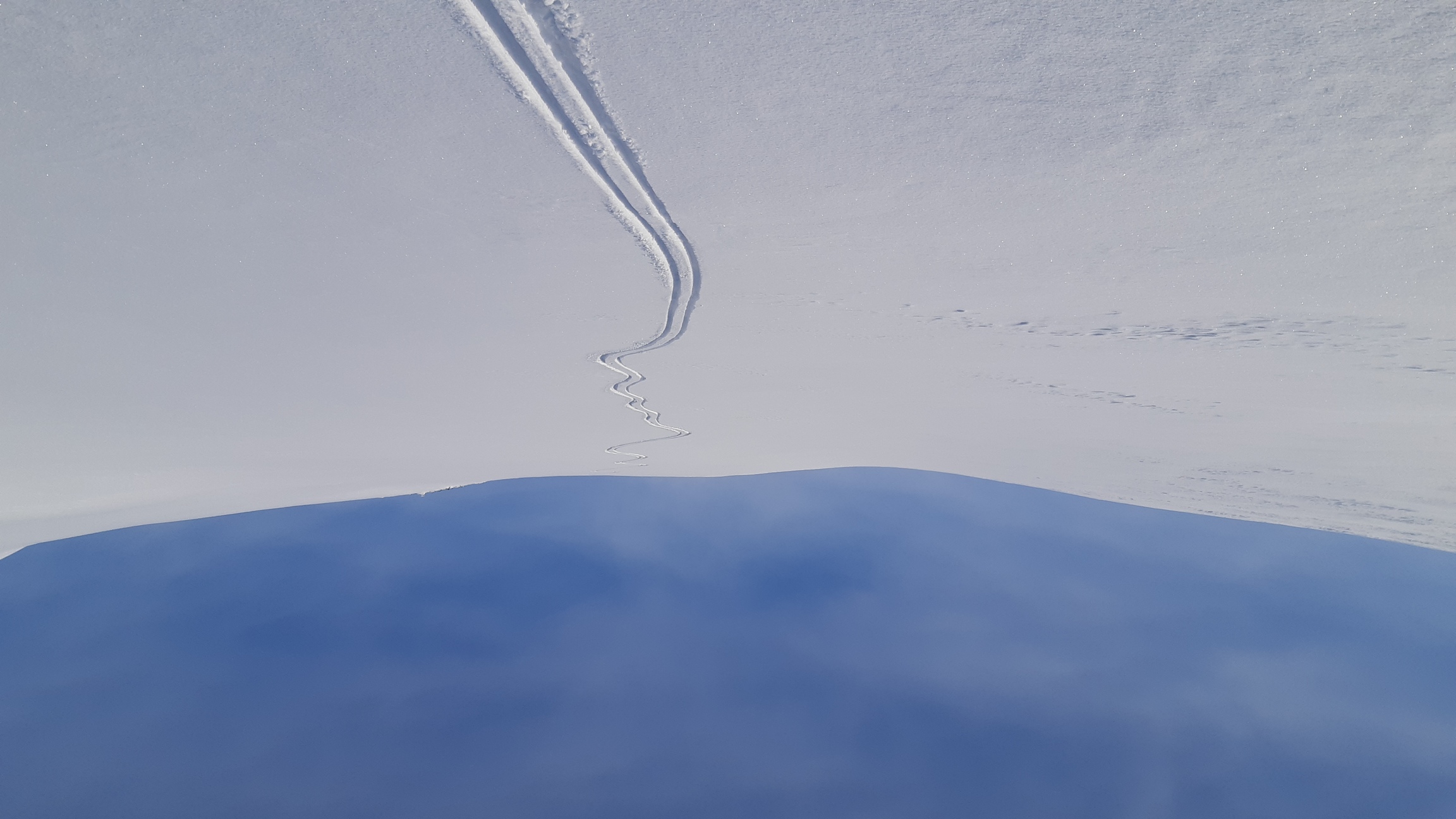

Inspired by this lovely sight, I quickly improvised a route that would take me up onto higher ground. Given my current position, however, it took me most of the first sunny day to just reach a suitable way to ascend - a narrow gully winding its way onto a plateau by the name of Luohttolahko.

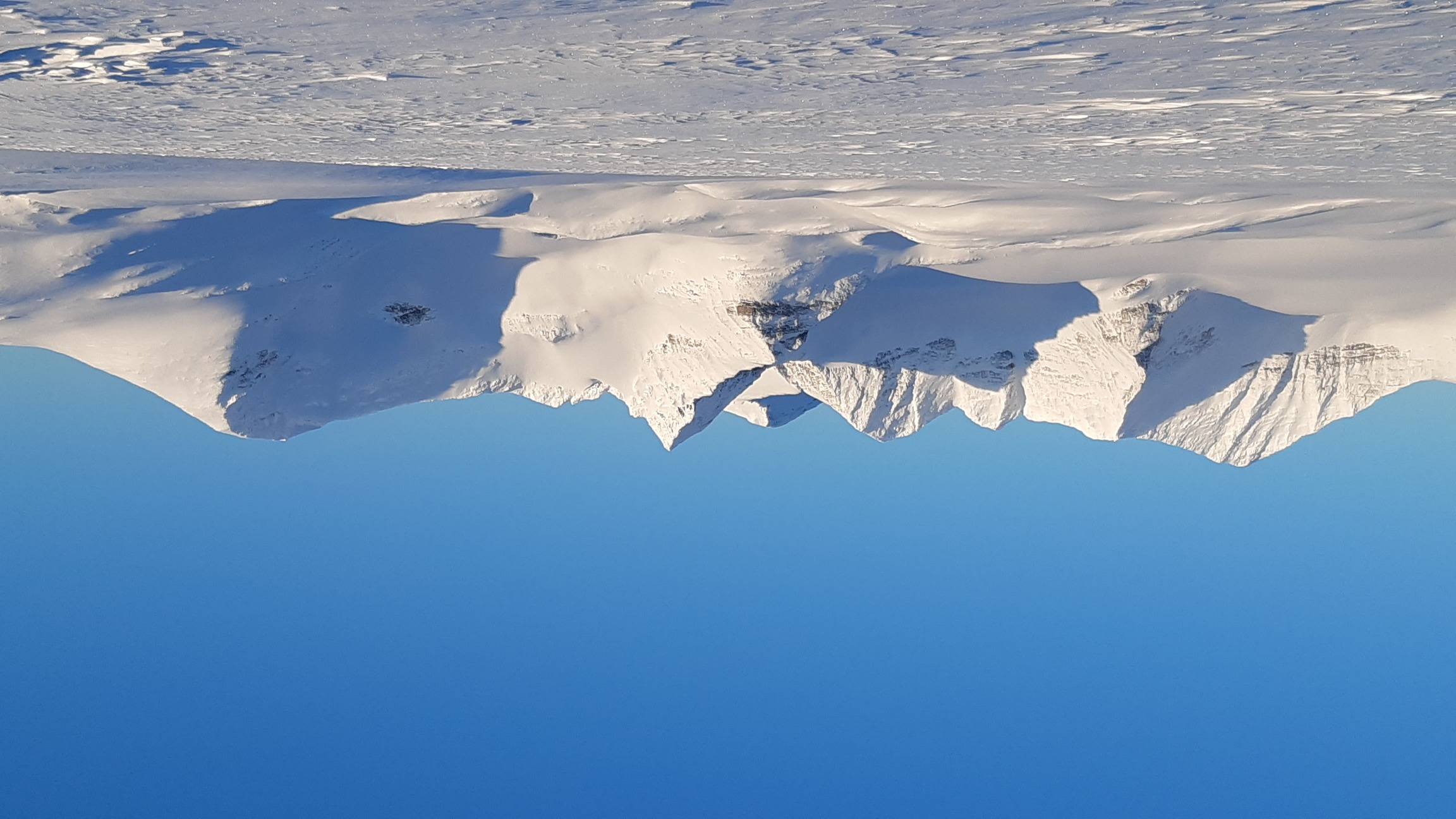

The way there was anything but boring, though. Going through Sarek's deep valleys with good visibility is a very different experience compared to stumbling through them blindly, in a snow cloud. I followed Njoatsosvagge - a deep, narrow valley surrounded by truly magnificent peaks and progressing through a series of long, narrow lakes. It looked so interesting on the map that I passed that way in the summer of 2019, but there was nothing but fog to see. This time around, though, the valley of Njoatsosvagge revealed itself in all its unpronunceable magnificence:

The bottom of the valley consists of a string of (frozen) lakes.

The bottom of the valley consists of a string of (frozen) lakes.

After hours of plodding through powder, I suddenly found clean-swept, icy and very slippery crust:

Skins helped a lot on such terrain, but sometimes the easiest solution was simply to take off the skis and walk on foot.

Skins helped a lot on such terrain, but sometimes the easiest solution was simply to take off the skis and walk on foot.

The last lake ends in a steep canyon. Such canyons are best avoided, as they often harbor hidden patches of weak ice and treacherous cornices waiting to collapse, just as this one did:

The valley then becomes broader and lower, eventually reaching Kvikkjokk 30 km further south:

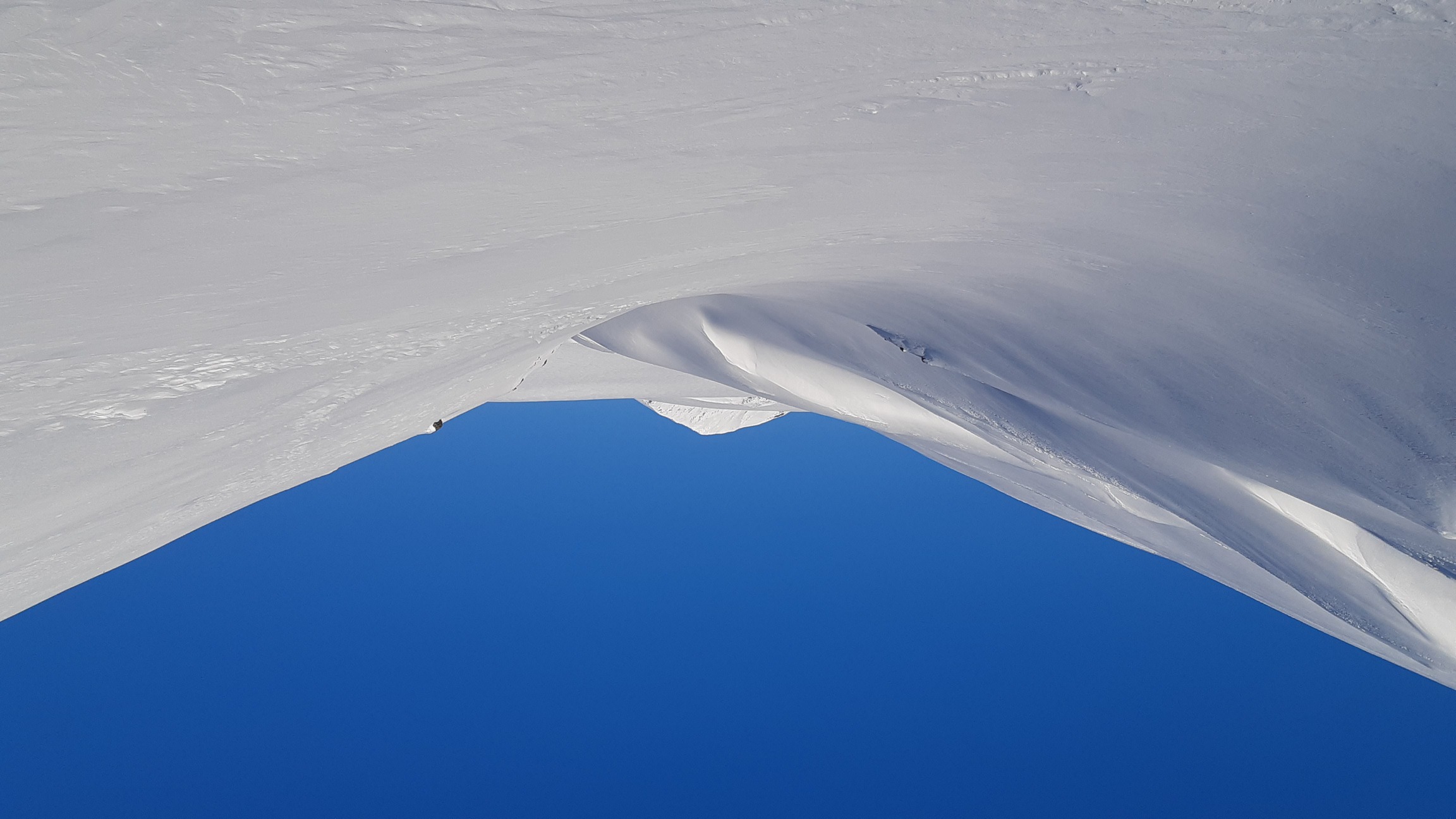

Given the good weather, however, I set my sights on the plateau of Luohttolahko, which is surrounded by some of Sarek's highest peaks. The first glimpse of the target - into the gully on the left and up, up, up:

It looks deceptively easy to follow such a gully. In summer 2019 it was quite a scramble. In winter, it's filled with meters of snow and is much easier to navigate, but with two provisos. First, the snow tends to be really deep and soft, and I mean REALLY deep - no skinny skis here. Second, there may be open water, cornices, and avalanches.

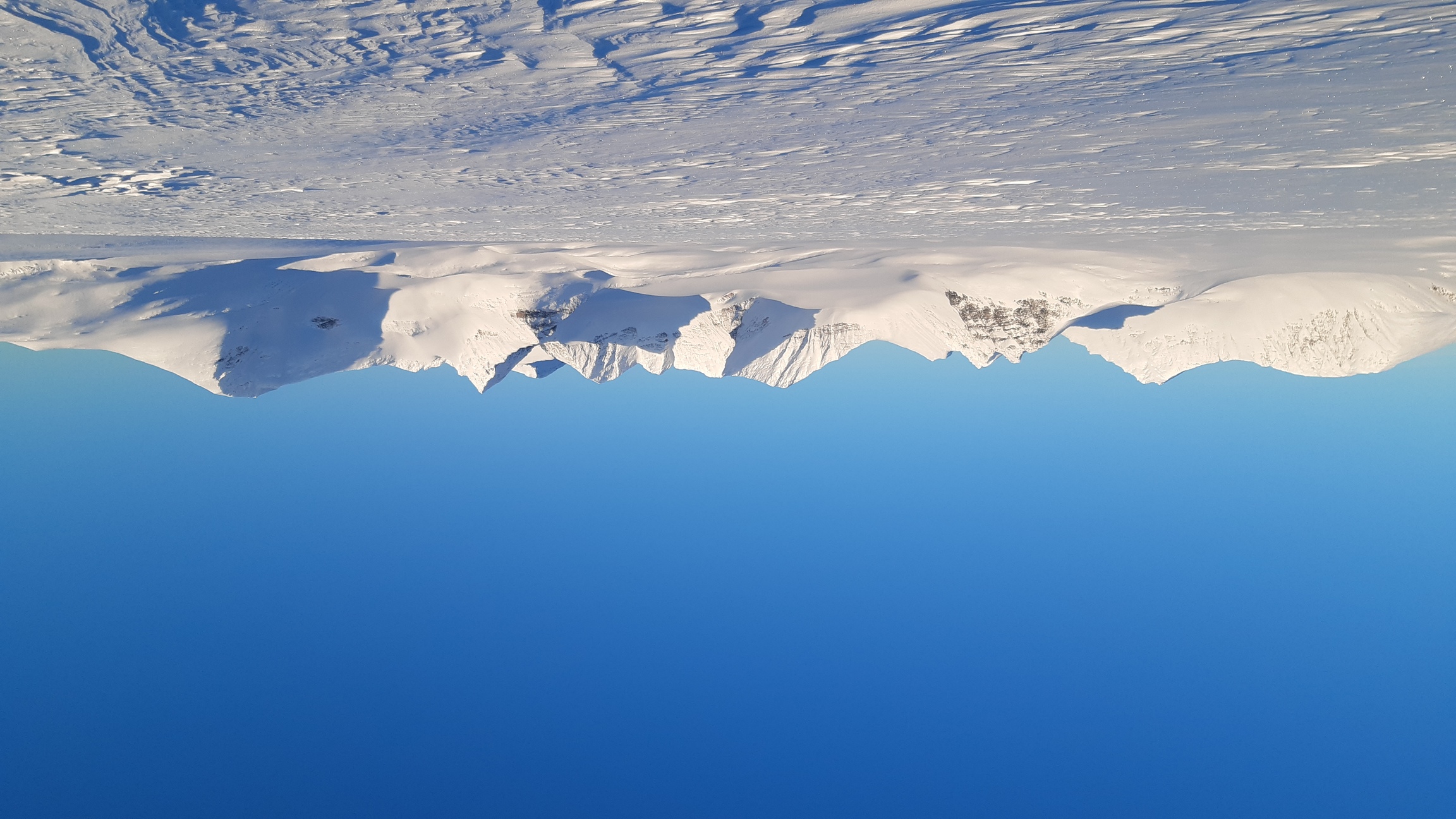

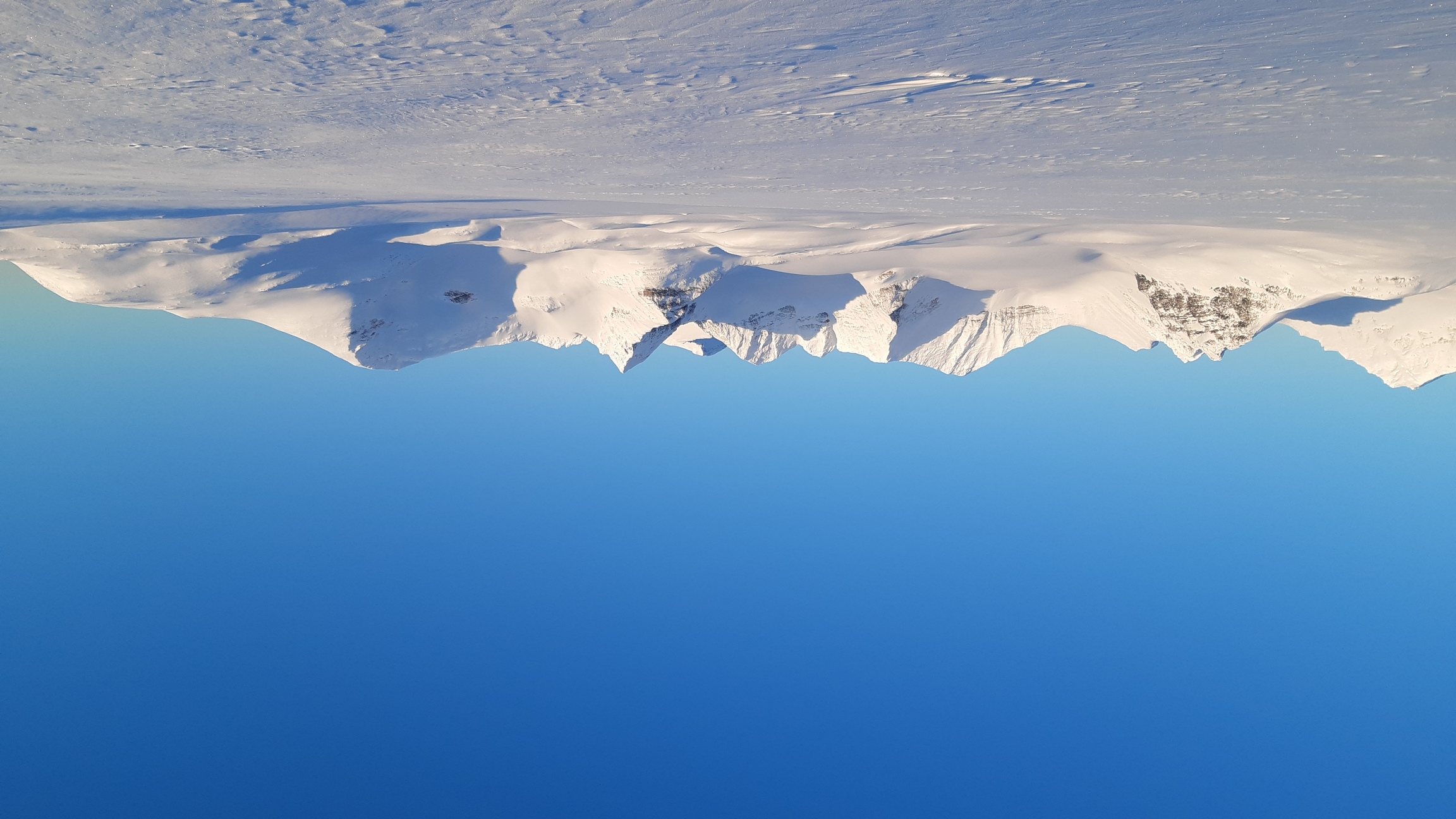

The views were worth it indeed. I was so desperate to use the good weather fully that I kept climbing until about 7 pm - my longest day on this hike - until I reached the top of the plateau at 1300 m and had 360° views of the peaks all around it:

The night at 1300 m with clear skies was a bit chilly. I had broken the thermometer, and my watch can't measure temperature below -15°C, but I would guess it was about -20°. Considering that the de facto temperature of comfort of my sleeping bag (Hyperlamina Torch) is at best -5°, I had to layer up with everything I had, including gloves. To put things in perspective, I tried and failed to melt a jar of peanut butter inside my sleeping bag that night - it was still frozen solid in the morning! It's an absolute credit to my parka and primaloft socks that I was nevertheless comfortable enough to sleep and recover my strength for another day of climbing. And the day dawned bright, promising good visibility and a chance to cross the passes to the east without having to descend back into the valleys!

I began by ascending a little 1500 m peak, which was the most direct way of crossing the mountain chain to the east. To me, this is the very heart of Sarek. I had a lovely time climbing here in 2015, when I summited the two peaks on the left-hand side of this photo and camped in the fairy-tale little valley underneath:

By the way, at 1500 m of elevation, the highest elevation I reached on this hike, I found fresh wolverine tracks! I followed them for some hours afterwards, as the beastie and I were apparently headed the same way:

After a hearty snack at the peak, I descended into Lullihavagge - a very narrow and steep valley that takes one over a 1350-m pass southeast, towards the large glacial valley east of the Pårte chain. It was fun to ski down slopes steep enough to require some turns. In fact, one spot was so steep (about 45°) that I only dared to descend because my friend the wolverine had already passed that way.

By the time I had descended from the pass, which proved quite uneventful as Lullivagge is not steep at all on the southern side, the weather did not look quite so promising anymore:

In fact, although I had no way of knowing it, that was basically the end of good weather for this trip. Very fortunately for me, I decided to make a snow cave, hoping to summit Pårte and then spend another night in the same cave. The summiting never materialized, but the snow cave proved extraordinarily useful to wait out the bad weather.

Days 6-7: hibernating and descending to Rapadalen

Digging the snow cave took much longer than usual - about 4 h - because the snow was packed very hard almost all the way down to the ground. On the other hand, I took the opportunity to improve my architectural skills and made a really spacious, comfortable cave with a fully sealed entrance. I therefore slept like a prince in this five-star establishment and woke up ready to tackle some serious peaks. But when I poked my head through the fresh snow piled over the entrance and wormed my way out - surprise! - I was in the middle of a cloud, with heavy winds and snow falling thick all around!

There was no question of climbing anything in such weather. I could have continued down the valley, but I was barely a couple of days away from Kvikkjokk now and had plenty of time, so I thought I would just stay put and wait for the weather to improve - a decision made much easier by the availability of an extremely cosy shelter all ready for me! Which makes me suspect that many a hiker has taken a day's break because their shelter was a little too comfortable. Anyways, I spent the morning improving the snow cave: I filled in the entrance and then re-excavated a smaller tunnel to make it even more storm-worthy and warm. Towards lunchtime I tried to practice telemark turns on the slope immediately above the cave, but the weather was so nasty and the visibility so poor that I quickly desisted - losing my shelter in the snowstorm would have been disastrous indeed. Instead, it was a day of idleness and repose: I slept, ate, slept some more, and relaxed as I had never relaxed on a winter hike before.

It was a struggle to dig myself out on the morning after the storm because the entrance tunnel was completely filled with fresh snow, but initially I had some hopes of better weather. So much so that I started to climb up the slopes of Pårte (2000 m). Unfortunately, within an hour I was back in a cloud, and when it began snowing and blowing again, I gave up and turned back down. It was definitely the right decision as I couldn't even see my own trail properly and had to exercise extreme caution on the way down, and furthermore, it continued to snow the whole day. Still, this was a disappointing moment and a difficult decision.

Considering the weather, I decided to just descend into Rapadalen and follow it south the next day unless the visibility improved. The valley of Gådokvagge looked very easy on the map, but in its lower reaches the stream flows in a canyon, while the slopes are in some places fairly steep. As usual after heavy snowfalls combined with strong winds, the conditions were freakishly variable: deep powder here, bare rocks there, and a lot of ice in between. So scrambling down through the fog proved slow and tiring work. I went in and out of the canyon multiple times, often on foot rather than on skis, before finally reaching Rapadalen and camping among its birch trees.

Days 8-10: Rapadalen to Kvikkjokk

Rapadalen is a huge, low-lying valley that provides easy access to central Sarek - at least in winter, when all the swamps and mosquitoes are frozen solid. It is overgrown with forests of stunted birch trees and, further down, pines as well. I had intermittently decent visibility on day 8 and so enjoyed some nice views of it. In fact, I toyed with the notion of ascending the slopes to the famous viewpoint at Skierffe, but it was snowing half the time and the peaks were mostly covered in clouds, so I passed. In addition, breaking trail through the forest was slow work, although a strong icy crust about 30-40 cm into the powder helped a lot. In general, I would say that this valley would be nearly impenetrable after a few weeks of snowfalls without a thaw: last year, for instance, it would have taken me twice as long, if not more, to do the 15 km to Kungsleden that this year I covered in merely 8 h. If you think that 15 km in 8 h is nothing to brag about, remember that we are talking about breaking trail through a forest - there is little wind here to create a crust or compact the snow, nor are there any straight paths.

Some more views of Rapadalen:

One unforeseen obstacle was the river itself, which turned out to be only partly frozen and divided into multiple branches. I managed to cross over ice, but not without going up and down each of the several larger streams looking for the strongest ice. Then towards late afternoon I started to meet the first H. sapiens since day 1 and soon after that reached Kungsleden. Compare the numbers: 8 km along Kungsleden at the end of a long day took only 1.5 h, while I worked much harder for 8 h for the first 15 km through the woods. Thus: it's extremely difficult to estimate daily progress when planning such trips; it all depends on snow conditions and the availability of some trail.

The next strech was mere routine. Since I still had a couple of days and was hoping for better weather and some fun on the slopes, I headed for Kabla national park instead of following Kungsleden to Kvikkjokk. The evening was relatively calm, especially in the dense forest where I camped. For the first time on this trip, I even cooked outside the tent and enjoyed a peaceful meal out in the open at sunset before turning in:

Two things caught me completely by surprise. First, despite the quiet evening and signs of better weather, the night was one of the coldest on the entire trip, again way below -15°C. Second, when I happily started climbing the snowmobile tracks that led over the top of Kabla in the morning, hoping to have some fun on the slopes above, it started snowing and blowing again. Still hoping for the clouds to lift, I very nearly reached the first top (1100 m), climbing from 470 m in about 2 h. Once I approached the top of the ridge, however, the northern wind reached such speeds that I was twice thrown off my feet although I was by then walking on foot and carrying the skis. The situation was beginning to look unpleasant, so I stumbled (quite literally) back down the slope, now facing the fierce wind. It seemed like a waste of climbing effort to descend all the way back to Kungsleden, so instead I tried to hide between some favorably located lower peaks. Indeed, there was a well-shielded corner at ~900 m of altitude where it proved possible to pitch my pyramid and anchor it to some bushes. I shoveled tons of snow, making the tent as storm-worthy as possible, and crept inside to hide from the weather (but not before developing a touch of frostbite on the windward cheek, as it later transpired). As the wind was howling and the tent shaking, I once again snuggled up in my sleeping bag and relaxed, although this time only for half a day.

Since it was still blowing and snowing next morning, my hopes of taking the high route to Kvikkjokk over the Kabla range evaporated, and I just followed the snowmobile trail over the main ridge. Once back to lower altitutes and below the clouds, it became more tempting to improvise, so I left the trail and made for Kungsleden through the woods, trying to stick to open lakes whenever possible:

The snow was much deeper than in Rapadalen, but again there was an icy crust buried deep under the powder, creating a rather weird surface to ski on:

Considering the deep snow, I was very relieved when I finally reached Kungsleden just north of Kvikkjokk. My bus was leaving at 5 am next morning (the lovely transport connections again), so I just whooshed down to Kvikkjokk to kip there. Mischief managed! And thank you, Sarek! :))